Questions

I came up with the questions of

- What is the scale of the system?

- What are some of the key features

- Do we need to provide same day confrmation?

- Is there a possibility of overbooking? If so, what should we do

these were some additional suggested questions

- Do we need to support other channels of booking?

- Do customers pay in full when they make reservations?

- Do Hotel prices change dynamically?

We can do some rough estimation that with 5,000 hotels and 1 million rooms in total

- About 70% of the rooms will be booked and the average stay duration is 3 days.

- This leaves us with about . We can use this to calculate a rough TPS of around transactions per second to book a hotel room.

Design

We need to support the following features

- View Hotel/Room details

- View Booking page ( Users can confirm booking details )

- Reserve a room: Users click on a book button to reserve and book a room.

If we assume that we have around 3 TPS to book a hotel room and only around 90% of users drop off the flow before reaching each step, then we can assume that

- 3 QPS to book a room

- 30 QPS to view booking page

- 300 QPS to view Hotel/Room details

This means that we have a high read/write ratio. A relational database provides ACID (atomicity, consistency, isolation, durability) guarantees. ACID properties are important for a reservation system. Without those properties, it’s not easy to prevent problems such as negative balance, double charge, double reservations, etc. We can also shard our database by hotel id if it becomes overloaded.

High Level Design

We need a total of 3 different subgroups of APIs - Hotel, Room and Booking

-

GET/POST/PUT/DELETE: To update and get information on the hotels

- GET /hotels/ID : Get specific hotel

- POST / hotels/ID : Add new hotel

- PUT /hotels/ID : Update hotel

- DELETE /hotels/ID : Delete hotel

-

GET/PUT/POST/DELETE : To update and get information about rooms in the hotel

- GET /hotels/ID/rooms/ID : Get details information about a room

- POST /v1/hotels/ID/rooms : Add a room

- PUT / v1/hotels/id/rooms/id : Update information about a room

-

GET/POST/DELETE: To update information about reservations

- GET /reservations : To get reservation history of the logged-in user

- GET /reservations/ID : To get detailed information about a reservation

- POST /reservations : To make a new reservation

This can be supported by the following system

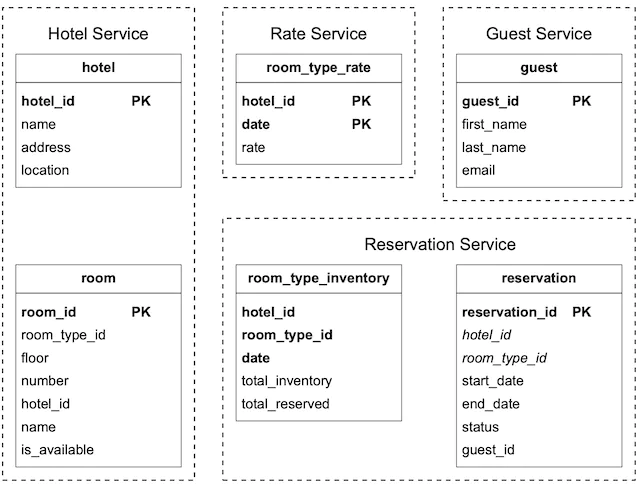

And a database schema as seen below

Reservations

We can support a reservation table by storing the data in table called room_type_inventory: the total number of rooms avaliable for the specified hotel_id, room_type_id, and date.

This makes it easy for us to manage reservations within a date range. Assuming that we have 20 types rooms per hotel, we would generate about million rows. This is well under the capacity of a modern databases like Postgres which can handle billions of rows.

We can achieve high availability by setting up database replications across multiple regions or availability zones. Eventually, we can also set up a batch job to remove old reservations which are not as frequently accessed as current or future reservations. If that is insufficient, we can also do database sharding using the hotel_id as a key to shard.

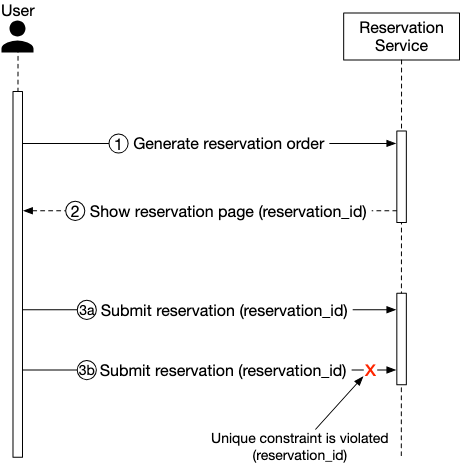

Idempotent Bookings

Since our system runs as a distributed database, we can have potential double bookings. We’d want to ideally have idempotent bookings - which means that even if users submit multiple booking requests, we only submit one.

We can do so by using a reservation_id that is a unique identifier which corresponds to each booking request.

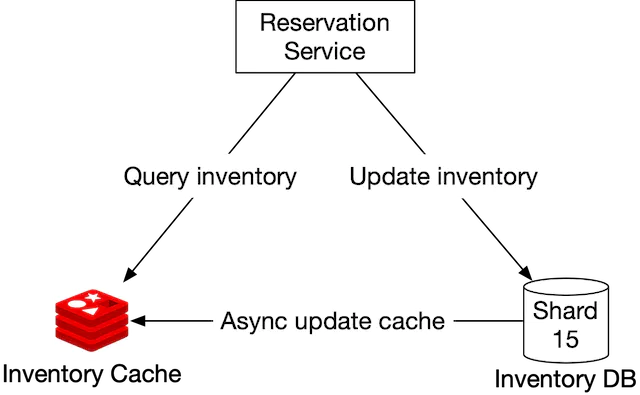

Caching

The hotel inventory data has an interesting characteristic; only current and future hotel inventory data are meaningful because customers can only book rooms in the near future.

So for the storage choice, ideally we want to have a time-to-live (TTL) mechanism to expire old data automatically. Historical data can be queried on a different database.

In such a case, we can utilise a service to automatically update our cache whenever there are changes in our db. Our cache can store information on the number of available rooms for each hotel given a room type and a date.

However, this will introduce slight inconsistencies in certain cases since our cache will always be behind our database in terms of data validity.

Concept

Race Conditions

What happens if we have two users who want to book the same room type and we have only one room of that type left? There are three potential ways to solve this - pessimistic locking, optimistic looking and using a database constraint.

Pessimistic Locking

When we perform a transaction on a row, we lock the row. Therefore other users cannot make edits to that row until we have finished our transaction.

It is easy to implement and it avoids conflict by serializing updates. Pessimistic locking is useful when data contention is heavy. However, it is difficult to scale since it prevents other transactions from accessing the resources.

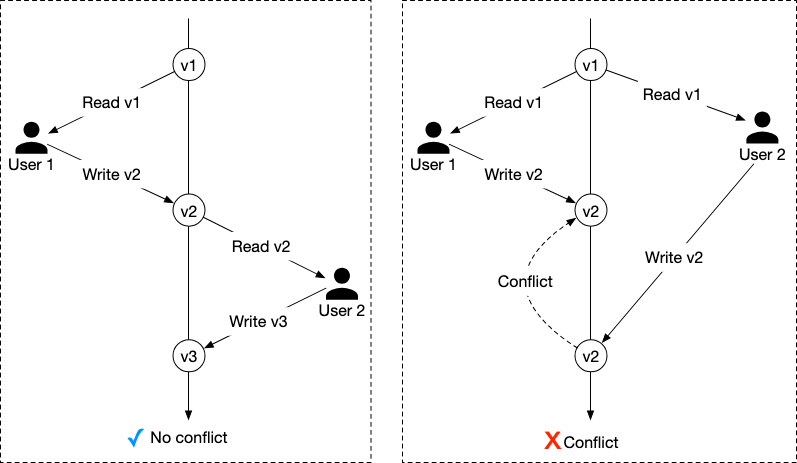

Optimistic Locking

Optimistic Locking allows multiple concurrent users to attempt to update the same resource. It does so by using a version number or a timestamp - versioning is preferred since timestamp can differ depending on server.

We can implement this in our database using a version_number column in our db. This allows it to be faster since we do not lock the db BUT might potentially result in an unpleasant user experience since there is only one single potential successful write per round during periods of high QPS.

Database Constraints

We can also implement a database constraint for specific operations. In our case, before we try and make a reservation, we need to validate that there are sufficient rooms.

CONSTRAINT `check_room_count` CHECK((`total_inventory - total_reserved` >= 0))

In this case, making a reservation means modifying our room_type_inventory table.