A Rate Limiter is used to control the traffic which is handled by a client or service. If a API request count exceeds a threshold defined by the rate limiter, all the excess calls are blocked

Rate limiters are important because they

- Help to reduce potential Denial Of Service (DDos) attacks

- Ensure we allocate more resources to high priority APIs

- Prevent our servers from being overloaded

We are going to be using the same framework as specified in the System Design Interview Framework.

Questions

Here are some useful questions to consider asking when understanding the scope of the problem

- How are we performing the rate limiting?

- On what side are we performing the rate limiting? -> Is this going to be a client side, server side or a middleware implementation

- How many users/load do we need to support

- Do we have to implement potentially different rate limits by service.

Background Knowledge

Redis vs DB

For something like a rate limiter, we would prefer using something like a redis cache instead of a database. This is because in-memory queries will be significantly faster than that of a database which needs to write and save operations to disc.

Location

Generally our rate limiter is placed on the server side. This is because client-side implementations are unreliable and can be easily forged by malicious actors.

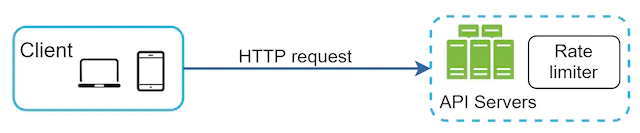

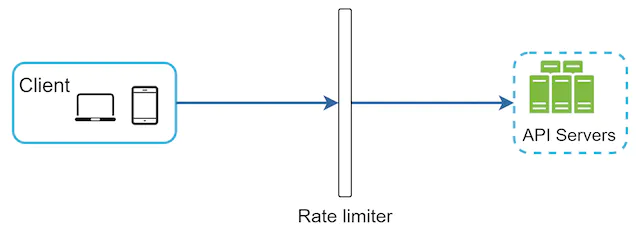

Therefore, we commonly add our rate limiters on the server side. There are two ways to do this

- We can add our rate limiter as a service that is used by our APIs

- We can use an API gateway which acts as a middleware. This gateway then throttles requests to your APIs.

Algorithms

Therefore are 5 main algorithms to know when it comes to rate limiting. Here is a quick synopsis of their pros and cons

Algorithm | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|

| Token Bucket | Easy to Implement, Memory Efficient and allows for a burst of traffic | Challenging to tune Bucket Size and Token Refill Rate reliably. |

| Leaking bucket | Memory Efficient ( Given a limited Queue size ) | Older requests might request in newer ones being rate limited AND parameters might be difficult to tune |

| Fixed Window Counter | Memory Efficient, Easy to Understand and good for specific use cases | Spike in traffic at the edge of the window could cause more requests than the allowed quota to go through |

| Sliding Window Log | Accurate Rate Limiting | Consumes a lot of memory since we keep track of every single request |

| Sliding WIndow Counter | Smooths out spikes in traffic and memory efficient | Assumes that requests in the previous window are evenly distributed and hence might not be reflective of the actual prev rates |

Token Bucket

A token bucket is a container that has a predefined capacity with tokens being put into the bucket at preset rates periodically. Once the bucket is full, no more tokens are added.

Each request consumes a single token. When a request arrives we check to see if there are enough tokens in the bucket.

If there are insufficient tokens, we drop the request. Else, we process the request and remove one token out for each request.

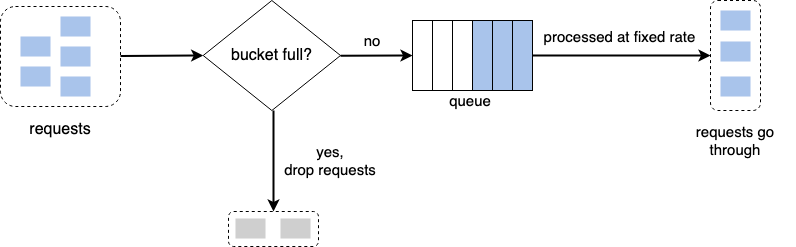

Leaking Bucket

This is used by companies like Shopify at the moment which uses it for rate-limiting.

We define a first-in-first-out(FIFO) queue which has a fixed size. This limits the number of requests which we can process at any given time. If our queue is full, then we drop the request.

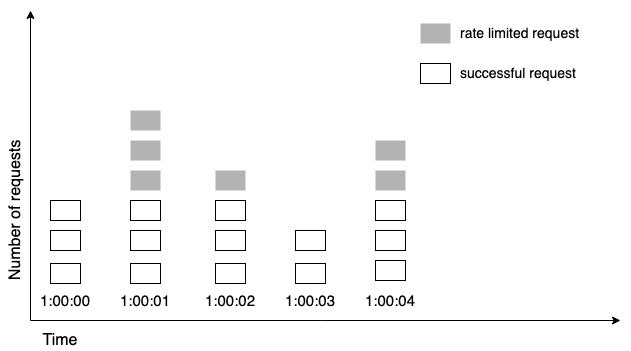

Fixed Window Counter

We divide the timeline into fix-sized time windows and assign a counter for each window. When a request comes in, we verify to see if its assigned window has enough capacity.

If there’s no more capacity, then we drop the request. Otherwise, we allow it to go through.

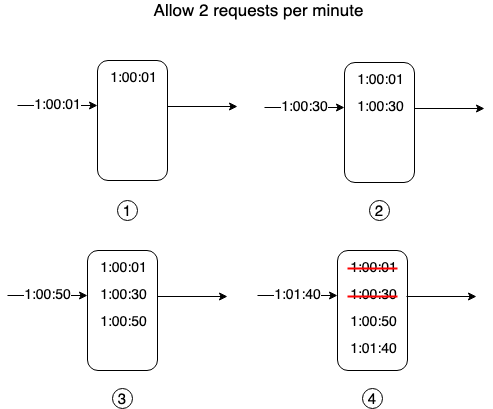

Sliding Window Log Algorithm

We keep a log of all requests that have been received. When we get a new request, we add it to the log, remove outdated request logs that are out of the window and only allow it to pass through if there is enough capacity.

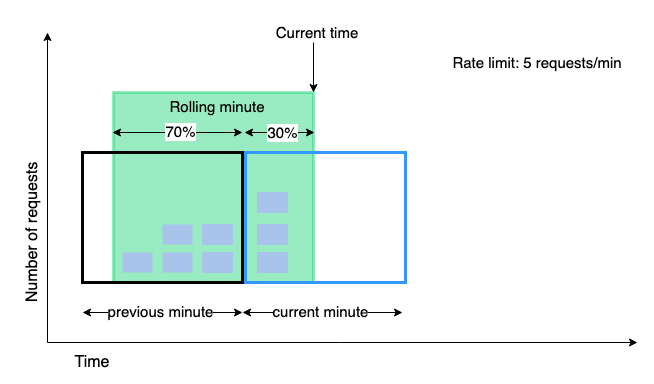

Sliding Window Counter

We define timeframes similar to the Fixed Window Counter - eg. 9:01 - 9:02, 9:02 - 9:03 and define a window size (Eg. 1 minute ). When we get a new request, we find out whether our request overlaps with another window.

Eg. If we’re getting a request at 9:01:30 and we have a window size of 1 minute, then it is intersecting the 9:00-9:01 and 9:01 - 9:02 windows. In that case, we find out how many request we’ve obtained in our 9:01 - 9:02 window first. We then add in the number of requests we received in the overlapped portion of the previous window.

Once we have this new request figure, we determine if it’s lower than the number of requests which we allow per minute. Else, we throw a 429 and reject the window.

Distributed Architecture

Race Conditions

When we build a rate limiter in a distributed environment where the execution of events is not guaranteed, we have a possible race condition that is difficult to work with.

For instance, take the following example where we have a redis cache with two operations

- GET - gets the curr counter

- SET - sets the curr value

If we have two processes trying to read from our redis cache

# Notation is Process : Operation -> Result

1 : GET() -> gets 2

2: GET() -> gets 2

2. SET(2+1) -> sets as 3

1. SET(2+1) -> sets as 3

This is an error because our redis cache should instead be set to 4 since we have processed two requests.

Simple solutions to this are locks or reconfiguring the cache to use atomic operations (Eg. batching GET and SET in a single call. We can also use Lua Script and sorted sets in Redis to solve this.

Synchronisation

When we migrate to use multiple rate limiter servers, we need to make sure that they all have the same request count.

This can be done with either an eventual consistency model ( in the event that we are using a multi-data center setup ) or by using a centralised redis cache to store the request counts.

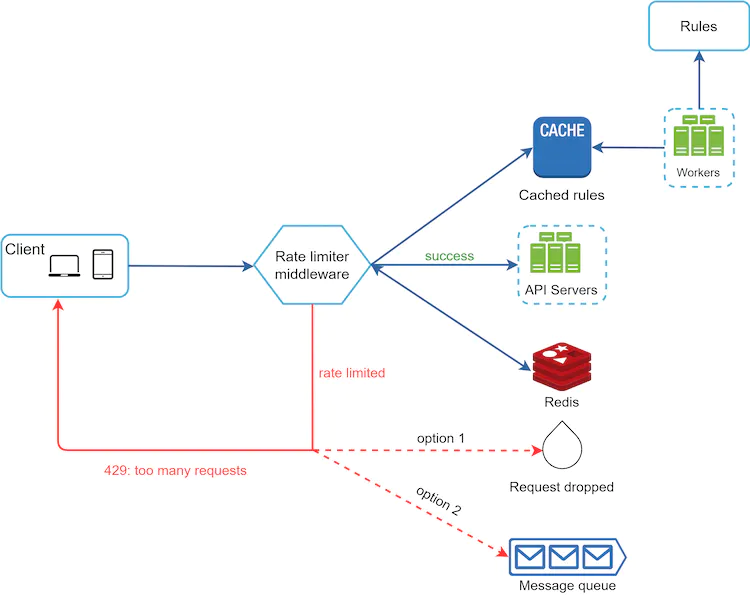

Design

Eventually, what we want is a system that looks like the one below

Depending on the requirements of the interviewers, we can modify this setup but this is probably the optimal solution to arrive at for now